PART 4Some names and details have been altered to protect the privacy of individuals.July 8, 2024 - Newton's first law: An object at rest remains at rest, or if in motion, remains in motion at a constant velocity unless acted on by a net external force.

This is what I think in the morning as I fight back tears. Can’t stop; won’t stop. I am a ball of energy barreling around my apartment—threatened by lateness from minutes that make no difference. Another day; another race.

The thought of the therapy session awaiting me this evening pains me: acknowledgement—deceleration—the net external force I run from.

Again I am reborn. I have come to hate this process—dragged from one womb, yanked from another—just a fingertip’s length out of nirvana’s reach. Today is my first day on the otolaryngology1 service, and I have a twin brother: Zaad, a co-student whose presence eases my jumpiness. We are brought home into the ENT workroom, which is decorated like a kindergarten classroom, with cut-out faces of the ENT surgeons pasted to the wall and a birthday poster with a cupcake for each month of the year. Three tiny girls in blues file into the workroom along with us, just in time for our playdate.

“Don’t they look so young,” Zaad whispers to me. I nod, glancing at the flock of plausible pre-teens. Swallowed by my too-big, rumpled white coat, I wonder if people think the same looking at me.

We make the trip from the third floor patient rooms to the fourth floor. On the way there, we run into another group of blues. Wait, did you see that patient in room 80? A good morning cut short: we promptly march our way—one by one—back to the third floor. Hurrah!

Our presence eventually acknowledged, Zaad and I are paired with Natalie, a fourth-year medical student on her month-long sub-I,2 and we follow her into the surgical pre-op area in anticipation of witnessing our first case of the day: a partial thyroidectomy. For now, all is well; the family is together.

“You’re a trooper,” says Zaad in response to my horror stories. Yes I am, I think, and I’ve got the scars to show for it.

It’s nearly surgery time. The three of us walk up to the patient’s slot, ready to introduce ourselves in biblical angel-fashion—Do not be afraid—evoking a similar shock as those thousand-eyed beings with our dangling MEDICAL STUDENT tags. But that would be too predictable—too simple of a plot for the unseen writers of my life’s script.

So, instead, we are stopped by Adam, one of the chief residents—a man with a tense face and gummy smile. He looks at Zaad and I: “Which one of you is on Head and Neck?”

“We haven’t been assigned yet,” I say.

“I see. Dr. Scott usually gives us a heads up when we have students, but I guess she forgot.”

This time when he looks, it’s only at me: “Let’s just say you’re on gen/peds.”

And just like that, he breaks up our happy home. Goodbye Zaad; Goodbye Natalie. Again: I’m alone, orphaned. Again: I’m rushing to another end of the hospital—to another alternate dimension—with nothing but my scrubs and hourglass sanity.

I paste myself into the new OR like a sticker. Nice to meet you, Victoria; how about you write your name on the board? Can you help me wheel the patient? Hi Leo, I’m going to give you your cocktail now3—what’s your favorite drink? A mojito? Reminds me of vacation. Yes, this is definitely going to be a vacation. Hi, medical student? Cool. You were just kind of standing there in the corner.

Back in the OR, my past stand-in-mother—Taylor, one of the breast scrub nurses—spots me twirling on a stool.

“Is that Vicky? That’s my girl,” she says to Jennifer and Mia, the two ENT scrub nurses in the room. “That’s me and Dr. N’s girl. Be nice to her.”

Taylor zooms in on me with her cat-eye glasses: “You got a good team here. Jennifer might get on your case—she gets on all our cases. I think she’s a little psycho.”

Despite the playfulness evident in Taylor’s whisper, Jennifer does not smile, her ten-hut eyes—framed by purple-rimmed goggles and wrinkled beige skin—stuck in their irritation.

“Jennifer, take care of Vicky. Vicky, take care of Jennifer. You’re a team.”

From me: a nervous laugh. From Jennifer: nothing.

“You know my name is Jennifer too,” Mia says to Taylor. “Mia Jennifer.” Behind the mask, she reminds me too much of my actual mother—same short stature and bright eyeshadow. Same mastery of defusing. I give her a mental hug.

“Well, take care of Jennifer times two,” says Taylor and then she’s gone.

Welcome to the wild, wild west—where sleeping faces go uncovered, no longer hidden beneath towels and drapes. Where we leave slime trails of lube in their dead eyes. Where we ski the slopes.

Everyone—including Ezekiel, a PGY-4—is scrambling to get the room set up. Is he gonna use cocaine? Then put the cocaine! We’re still waiting for the cocaine.

“Jennifer, show him,” says Mia.

“I don’t know how to do it with the sticks! He does it.”

In my head I run iteration after iteration of what the attending surgeon—Dr. Lima, this mysterious he—could possibly be like. Tall? Short? Young? Graying? And then in he walks: a calm-toned man with owl-eye glasses. I walk across the OR to introduce myself and he shakes my hand.

“I have some cocaine, doc,” Jennifer says. “Do you want some?”

“Yes, we are going to use cocaine for the septum, because we won’t be able to get it into the meatus with sticks anyway.”

From Jennifer: “I tried to tell them. They ain’t wanna listen this time.” And—to Ezekiel: “No! We don’t use that.”

“C’mon, Jennifer, he doesn’t know,” says Mia.

“No, he’s been with me before, even if he didn’t scrub in.”

“For two years. Some people take a little longer.”

“Uh-uh.”

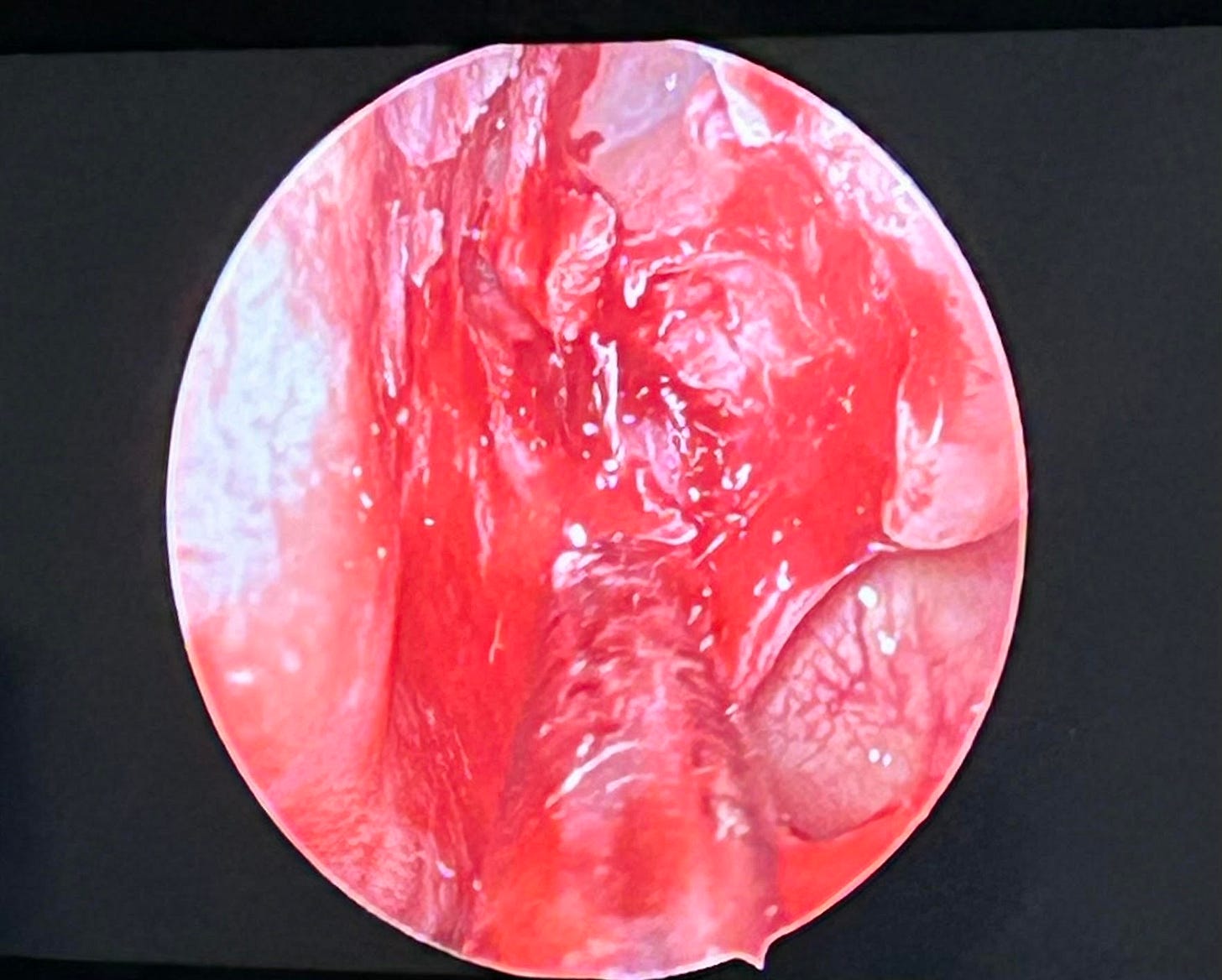

The attention is back to our sleeping patient, who we hover over like a kid ready to be tucked in. The view from the endoscope starts like a grainy prank video—zoomed in on the young man’s snoring face—before diving straight into his nostrils. Ezekiel wears another camera on his head that scans the skull down to the bone.

For hours, I am stuck in place, sitting on my corner-stool. Mia swaps with Joe—a bald white man—in time for her lunch break.

“And this is Victoria,” she says.

Joe waves at me and leans close: “Sorry about Jennifer; she’s a little crazy to be around.”

“Joe.”

“Feel free to contact HR.”

“Stop playing, Joe!” Jennifer says, giggling and aiming a bulb syringe full of saline. This is the first laugh I hear from her.

Suddenly the room is filled with a new wave of motion. Dr. Lima and I finally make eye-contact—once, twice—each look followed by a brief lesson on nasal anatomy. On the third look, he says, “Victoria, why don’t you come scrub in,” and I go through the motions, all too ready to jump back in.

“Okay, so paint the septum with cocaine,” Dr. Lima tells Ezekiel. “And the base.”

To me: “We use cocaine because it’s a good vasoconstrictor, so it can control the bleeding. It’s also a really good anesthetic and actually has some antibiotic properties—but we don’t care about that.”

“Of course, it’s not as good if you inject or inhale it.” Wink, wink.

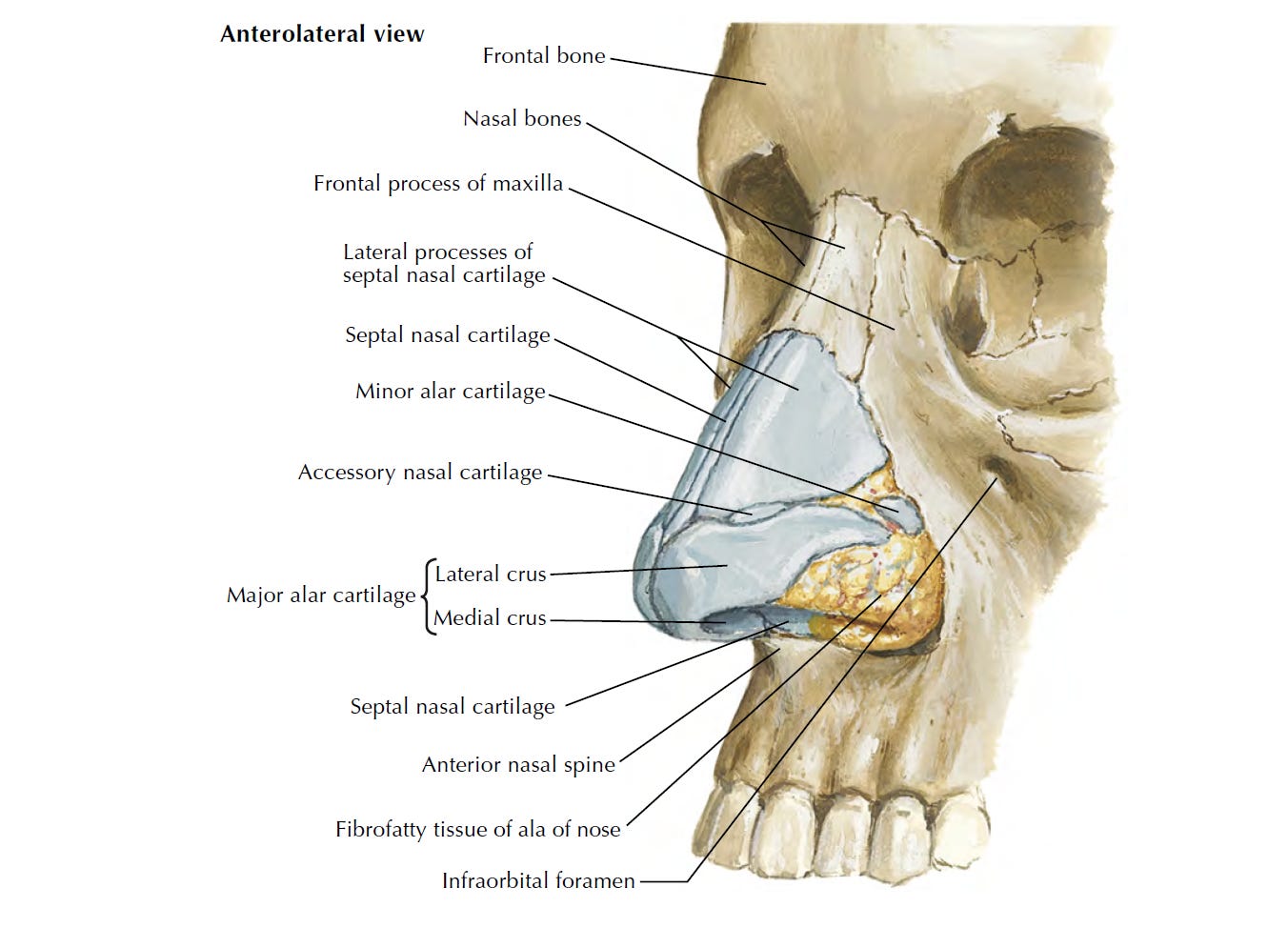

In the dark room we tend to our clay like tooth fairies. Give me your septum, and I will leave a little treat under your pillow. Dr. Lima passes me specimens pulled from the patient’s bloody nose for show-and-tell time. The way the rough edges of the maxillary crest scrape my fingers reminds me of a wood chip. Cartilage bends in my grip like plastic.

Two hours later and the surgery is done. The anesthesiologists take out their tube and the patient fights and flops on the bed like an out-of-water fish. Jennifer and Mia hold up a towel to shield us from the spray of blood.

Always watch yourself, especially when it comes to ENT. Yeah, ENT is a whole different world.

On ENT, we make our own music. In the pre-op area, a nurse next to me is shuffling papers and singing “Staying Alive.” There is no radio in the OR—just beeping, our organizing tune: He. Beep. Is. Beep. Still. Beep. A-beep-live.

Hitting flamingo poses on my step stool, I feel nimble. Graceful.

Dear patient, I hope you know that I am here and gentle. I lay down the tape on your eyes one micron at a time, careful not to tug on your eyelashes. Yes, that was me. Yes, I watch as they twist out your cartilage and staple your nose back together, how your body lay slack like a mannequin getting a tune-up. Yes, I put your blanket back in place when it slips. You don’t remember, but I do—how you groan like a zombie waking up.

“This is our third case, right?” Jennifer says to me, patting me on the shoulder. Somehow she’s right. Somehow I’m looking at how much Ezekiel’s eyes look like my little brother’s. Somehow Taylor is back in the room—Remember her name, Jennifer, she’s the queen of ENT. She knows everything—and I’m chewing on a piece of gum from Mia and wearing a heavy pair of goggles and there’s a laser melting away at blood vessels. Somehow I’m on my way home.

The big question of the day: how are you doing?

“Good,” I say.

July 9, 2024 - The mornings never get easier. My grande mort—big death after big death—with no refractory period in sight.

Today I am veal pinned against the chopping block, one of two sacrifices scheduled to give a patient case presentation to my peers—my fellow surgery prisoners—and Dr. Posy, the surgery department’s own resident villain. Near the parking garage, a pigeon circles overhead and the omen is not lost on me. Strangely, I feel no tinges of anxiety. In my khakis and sweater and white coat, I am competent—confident. This remains true throughout the duration of my talk. By the end of it, everyone, including Dr. Posy is blinking back at me.

“Wow, Victoria, I must say that this was very detailed. I don’t have anything else to add,” he says.

“Yeah, well, Dr. Newbaum taught me a lot!”

“Yes, it’s hard not to learn from her, right?”

Then later: with his smirking head held high and suited chest puffed with proud air, he walks out of the conference room without a word of goodbye or farewell. He’s just going to leave without saying anything? Great job to the presenters. Yeah, that was actually amazing. You guys set the bar so high.

In the elevator, I get one last pat on the back: “You did so good. You sounded like a breast surgeon.”

“Maybe that’s my future,” I say and laugh and rush out to get changed into my blues.

Today is kiddo day, and I once again find myself journeying to new lands: Leaver, the children’s hospital. Inside, the lights are dull and the walls are drenched in whimsy: cartoon snowmen, minions, Cars characters, Princess Elsa. They tell me, “Aww phooey” and “Friendship is the best medicine.”

The first new face of the day: Dr. Smith, a pediatric ENT surgeon with lidless blue eyes and a sweet squeaking voice. The second and third: Lily—a PGY-2 trailed by a long ponytail and a fanny pack—and Clarissa—a bright-eyed MS24 here to shadow for the day.

The theme of the day is tonsils. The OR—warm and cozy; my pearly gates after weeks of hellfire—threatens to lull me to sleep.

“This cute little lady—she’s six; she’s super cute—is having her tonsils removed,” Dr. Smith says to me and Clarissa. Here everyone is a cute little man—a cute little girl, a cute little guy. “They can just swell up—like two big marshmallows—and make it hard for them to breathe. So we take them out. And it’s not a terrible surgery to recover from when they’re so young.”

Clarissa’s contribution: “Yeah, my dad said it was his favorite surgery because he got to eat popsicles and ice cream all day.”

Our patient—a little brown girl with pink-and-white beaded braids and an unaware smile—comes in on a red wagon full of her favorites: a purple stuffed unicorn—it’s actually an alicorn, since it has wings—a bubble gun that she aims at our palms, and a book full of Disney princesses. Who’s your favorite princess? The little mermaid!

A few minutes later: the anesthesiologists are asking what flavor of sevoflurane5 she prefers. Cherry. I wonder what flavor I’d like to take me under. I’ll have what she’s having, please, I think, and make mine strawberry.

Our cute little girl is off to sleep, snuggled in a space-themed hospital gown, beneath a multicolored handprint blanket. Lily uses a mouth gag6 to force her jaw open into a scream. Clarissa and I hover over her shoulder as she cuts and burns into the space near cute little Brielle’s uvula.

“Okay, I’m giving you five minutes to clean the fossa while I pre-op the next patient. Don’t do anything crazy,” Dr. Smith says to Lily. “Are you gonna be okay?”

Lily nods, and Dr. Smith hugs two men in blues who wandered into the OR seconds ago—wow I haven’t seen you in years; you look all spruced up—before rushing out.

The music is back: soft pop songs to sway to as Lily char, char, chars.

“Um, she’s swallowing,” Lily tells the anesthesiologist. “She didn’t like that from me.”

Dr. Smith rushes back in and gives her five more minutes. Satisfied with her work, Lily sprays a bulb syringe full of liquid into cute little Brielle’s nostrils to clean up; it fills the gaping mouth like a bird bath.

“That looks so weird,” says Clarissa.

“I know, everyone thinks that this is some nice and pretty surgery. But it can actually look so barbaric.”

Back again in her now-you-see-me-now-you-don’t hustle, Dr. Smith takes Lily’s spot at the head of the bed. “I’m just gonna take a peekers.”

She finishes up the job and flies off to the next case. Clarissa and I stay behind with Lily to help transport cute little Brielle to the recovery floor. Coming out of her gas coma, she spasms herself awake, the bucking thrusting her tiny shoulder up and down. A cute little seizure. Clarissa hurtles around the room, helping out and doing things before I can even think of them.

At recovery, Lily tells the nurse, “I’m gonna have my student do sign out,” and gestures at Clarissa, who steps in front of me. I curl my stomped-on toes.

We get a brief break between cases, and I take the opportunity to nibble on some granola—my first taste of food this morning. I meet up with Lily and Clarissa at the refreshment station and sip on a paper cup filled with water. Before I know it, it’s go-time again and they’re off and I feel like I’m two steps behind. I quickly turn back to toss my unfinished water cup into the garbage and I get a dirty look—which I now collect like infinity stones—from a woman in a white coat sitting at the nurse’s station.

It is now Lilly’s turn to run—off to see an ED consult for an 11-year-old boy with a bead stuck in his ear.

“They tried to get it out with glue,” Dr. Smith says, rolling her eyes.

"Did it work?” says Clarissa.

“No.”

“It’s funny. I shadowed an anesthesiologist who also said he put beads in his ear. And I think he was eleven.”

“What is it about eleven? Six, seven-year-olds, sure. But eleven-year-olds should know not to put beads in their ears. That’s like middle school. I think I knew by then not to put stuff in my ear.”

“Boys are different, though.”

The locals of this land thrive on cute. They have gold eyeshadow and placenta pins. They take summer trips to Amsterdam for Taylor Swift concerts. Cute, cute, cute. I worry that I stand out with my shell-shocked gaze—how I struggle to place myself. I’m here and there in the next: Schrödinger’s med student—mind both nowhere and everywhere.

Time escapes as we speed through the day, with two ORs running at once—a revolving door of cute little bodies and tonsils and ear tubes. The new faces come with stories. How do you have two surgeons and none of their kids want to be a doctor? My son, he wants to be a hockey or football player—you know how hard that would be—or an artist. Not a hockey player; that’ll mess up his teeth. He already has messed up teeth, so he’s fine there. He’s still young, though; he has time to change his mind—it changes every year. I used to be in mechanical engineering, so it obviously still keeps changing. Whatever makes them happy.

“Why does the mouth stink so bad after surgery?” Lily asks Dr. Smith.

“All the scabbing and dead tissue.”

This kid screams and gags waking up. Then on to the next. Can you think of somewhere you’d like to be? Warm. So like, the beach?

The trio talk bad habits.

“You know these things?” Clarissa asks, squeezing the sleeping teen patient’s yellow stress ball, “I used to just bite them when I was like thirteen, fourteen. And one day I was biting it, and it just popped and got all over my face.”

Lily shares: “When I was like ten, I used to eat flowers on the field. I didn’t care! Then one day I found a rat’s tail in the grass, and I’m like, ‘I’m an adult now.’”

“You know those things on the side of the Nintendo Switch, that you can take out and play? My daughter will bite on them, and it just drives me crazy,” Dr. Smith says. “It’s a nervous habit. But I can’t complain because I bite my nails.”

Clarissa again: “My mom is so hypocritical. I pull my hair sometimes—also a nervous habit—and my mom will yell at me as she bites her nails.”

In my head: “Me too! I pick at my skin—scratch at scabs until they bleed—but scold my nail-biting boyfriend.”

Our current cute little man fights back against the restraint of the five adults pinning him down. Yeah, they get super strong. Don’t get kicked. He went to sleep mad; he was saying, I don’t like this. Those are usually the ones that wake up wild. He was a feisty one—so cute.

The next cute little pre-teen rolls in on her surgical bed holding a plush toy.

“Hey sweetheart,” says Dr. Smith. “What’s that? A fennel? Or an onion? Oh, it’s a garlic!”

“It’s not on your head anymore,” says one of the circulating nurses.

I almost pass out from exhaustion on my stool, nodding off for seconds at a time, my butt sliding towards the edge before making smooth recovery after smooth recovery.

The last patient of the day: a Chinese teen girl with two white parents who look at me with suspicion. Suddenly she cannot move her jaw, she utters, her tongue flopping around in its stiff cage.

“This doesn’t make any sense,” Dr. Smith says to me. “Nothing happened before this started? And she can move her face just fine? And why would she be numb?”

In the OR, Dr. Smith has me put my fingers in the girl’s mouth. My gloved hands rub against her fang-like teeth.

“Nothing’s wrong with her jaw. See how her teeth fit?” Dr. Smith forces the girl’s jaw shut and open again; I do the same. “Just bring it down and back. See, I can do that quite easy. We wouldn’t be able to do this if her jaw was broken. This still makes no sense. Neither does the numbness. This is something—something psych. There’s nothing to be done. How anticlimactic.”

“So we just intubated this poor child for nothing? This poor baby.”

July 10, 2024 - Today I am a dead woman walking. My patient one-liner: Victoria is a 23-year-old female who presents today because she says she doesn’t “feel well”—potential drug-seeking?—and that she’s “holding back tears.”

Waking up, I keep telling myself, “I can’t do it, I can’t do it,” and then I do it, and I don’t know whether to be proud or disappointed.

I am a chicken with my head cut off. At first I plan to head to M&M—the weekly general surgery I’m sorry conference. Then—whoops, nevermind—I learn that ENT doesn’t go to that. Rushing to the ENT workroom, I am a wrecking ball, a knocked-down “Caution Wet Floor” sign left in my heavy bookbag’s wake.

“Uh oh,” says a woman in scrubs walking next to me. And then: “good morning.”

“Good morning,” I say back, and then sprint on. Behind me—to another target—I hear, “Hope you have a happy morning!”

Okay, rounding-time: a good ol’ reliable good morning—whoops, nevermind. I’m with the wrong team—with Zaad and Ezekiel and Natalie and Chloe, another resident—and they’re not rounding. Actually, yes, they are. They race out of the room.

“Do I follow if I’m on clinic?” I ask someone in blues at the computer.

“Yes, you probably should. Clinic doesn’t start until 8 AM.”

Then I’m bursting out the door like the Kool-Aid man, yelling “Oh yeah!” and tailing the group before they scurry out of sight.

“Our first patient has Ludwig angina,” Ezekiel tells us. “Which is an infection that spreads throughout the floor of the mouth and can cause swelling that leads to airway obstruction. So we took him to the OR yesterday.”

The man’s face is stuck in annoyance. Drains trail down his neck like vines.

“How was the ice cream?” Chloe asks him, simultaneously checking the hanging tubes.

“I didn’t have any.”

“You didn’t like it?”

“They didn’t give me any,” he says, wrinkling his eyebrows. Chloe tries to flush one of his drains out with a syringe. The patient flinches. She tries again.

“Look, I’ve been very respectful. I know you see me as a specimen, but I’d appreciate it if you listen to me—to what I’m saying to you. You’re trying to insert something that’s not going in, and you keep trying it. And it snapped, because this one here isn’t all the way in. And it’s hurting my neck.”

“I hear you,” Ezekiel says to him. “We’re sorry about that. Next time we’ll be more gentle.”

The man shakes his hand. “No, it’s okay. I’m sorry. I just got a lot on my mind.”

Back in the workroom, they go through the Head and Neck patient list. This is a woman who got punched by her son for taking his phone away; she has an orbital fracture. This is a man who got pistol whipped at work. Yeah, “work.”

Another breakaway: a suture workshop for the residents that we students are invited to join in on. Hey, how’s your day? It’s early. Where’s Ezekiel? He was just like, see you there, but then he walked in the opposite direction. We’re like, where are you going? We’re all going to the same place. He’s so mysterious.

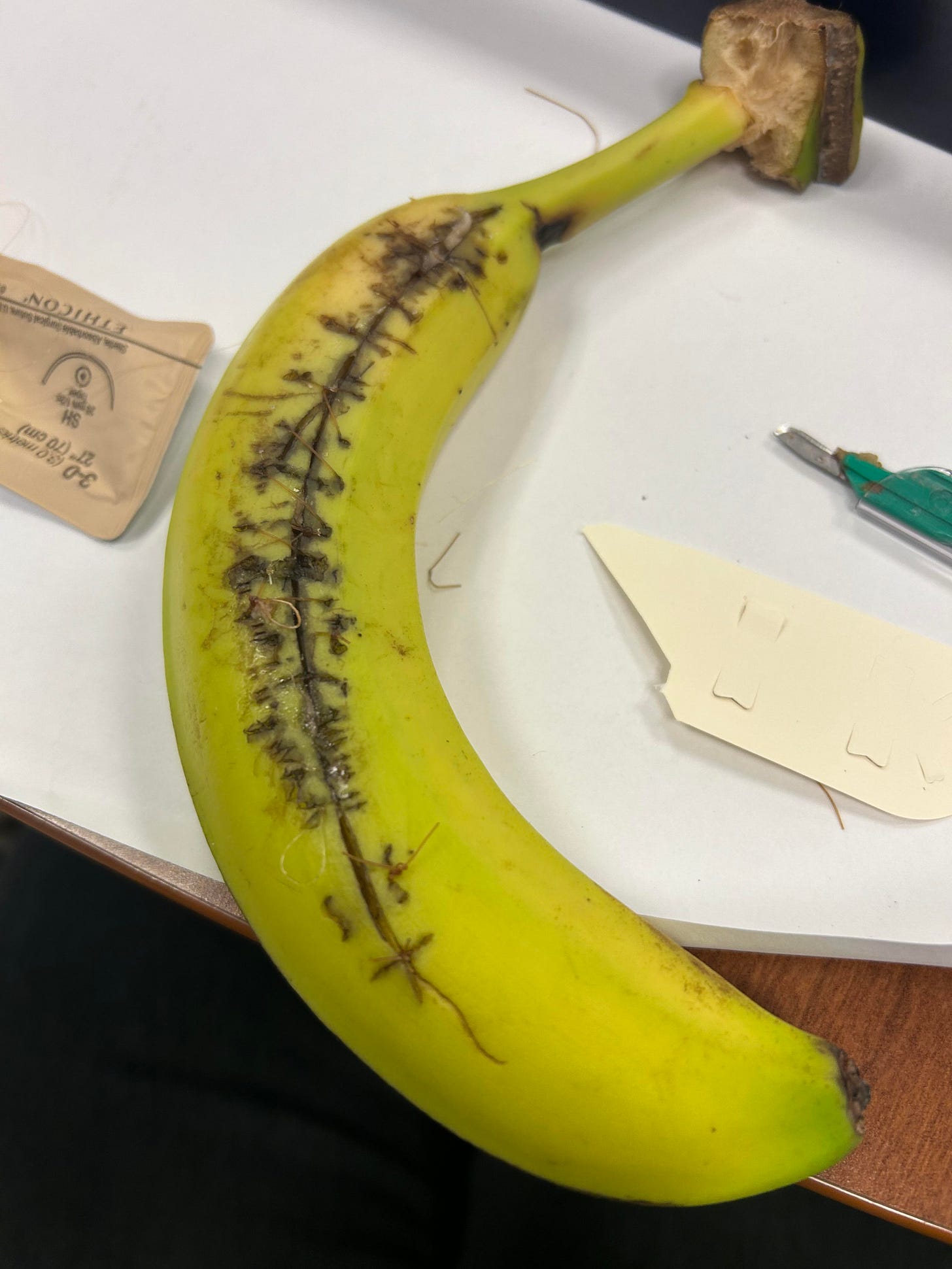

I am handed an unripe banana—my actual specimen—and fight the impulse to peel away at it. Grabbing a scalpel and forceps, I get to work, carving through the outer peel down to the soft flesh—gashing, wounding. Then I get out my needle and thread and make it all better again.

“It’s not too late to change your mind,” Ezekiel says to me. “Are you sure, Victoria? I see some good suturing skills.”

“Yeah, you’re a natural,” Zaad adds.

“I’ve been conflicted lately because I’ve been liking suturing and stuff. You know, using my hands.”

“If the shoe fits.”

“What do you want to be when you grow up,” asks Dr. Kirk—a graying Ms. Frizzle look-a-like.

“A psychiatrist.”

“Well we need more psychiatrists in the world. Just promise you’ll be a good one.”

“I promise.”

Then: my Frankenstein banana is tossed in the trash, and I’m following Lily up the stairs to Dr. Geng’s clinic.

“You can put your stuff down in here,” she says, leading me into the physician workroom. “Be secretive, though, because people do steal stuff. Like yeah, try to put it in the corner.”

And these are the last few seconds I have before the chaos begins. Dr. Geng is an ever-smiling, baby-faced father of one and a half. I’ll be going on parental leave soon—three months. Yeah, I’m trying to mentally prepare myself for the next one.

He tells me and Lily to go see the first new patient of the day together.

Outside the room: “What do you want to ask?” she asks me, and I regurgitate the notes I’ve managed to scribble down in the last handful of minutes. She nods and we go in.

The patient is a woman dressed in bright colors with a heavy smoker’s rasp. Feigning confidence, I smile and go through my questions. Now comes the next obstacle course: doing an ENT physical exam—something I have not done on an actor since last year. Something I have never done on a real patient.

Scared, I look at Lily between each step. “Go ahead,” she says to me, and, “Go on,” the tension in her eyes migrating down to her toothy smile, but I’m not sure exactly what to go ahead and do. Through sheer will and emotional regulation, something gets done. I fumble around for the appropriate materials—tongue depressor, otoscope, scope tips—and hope that I’m seeing what I’m supposed to. Then I’m out.

“Sorry, I’m a little slow,” I say to Lily.

“No, no, that’s okay. You’re good.”

In the physician workroom: How was your vacation? It was great; I got a really bad sunburn, though. You know, the type that itches? And I’m like, I look like I’m on meth. And then you sweat under the sunburn? Yeah. I just walked out of the office and there was a man peeing with the door wide open, and I ran away. Shit’s getting crazy.

I’m sitting two seats away from Maya, a visiting fourth-year medical student from Michigan, and Jasmine, a dark-skinned woman in scrubs with a wavy black-and-blonde ponytail.

“Yeah, I just started third year. This—surgery—is my first rotation.”

“How are you liking it,” Jasmine asks, her big brown eyes inflated with concern.

“It’s honestly been a lot. You know, getting dropped in all these new places and having to quickly adjust.”

“Yeah, clerkship year was hard. I’d never do it again,” says Maya.

“Yeah, I mean like, why the fuck do medicine?” Jasmine says. “It’s hard. It’s like prison. And you miss out on so much of your life. My daughter wants to be a psychiatrist, and it’s like, why go through all that rigmarole? Just become a psych NP7 and do what the fuck you want. Have some independence.

Like you’re paying to help people. That’s not right. And it doesn’t get better with residency. These residents, I feel so bad for them. They’re always talking about how much they hate this program. This one girl is in her second residency—in plastics—and she hates it. She wants to do psych now, but she didn’t get into the program she wanted and now she’s stuck.”

Then later: “Yeah, I was born here, in Chicago,” I say. “But my parents are from Nigeria.”

“You’re Nigerian! My kid is half-Nigerian. We’re losing the culture. Do you speak any of the languages?”

“No, my parents didn’t teach me.”

“What!”

“I know. They both speak different languages—my dad is Yoruba, and my mom is Igbo. And neither of them taught me, so I don’t know anything.”

“So they just have you eating egusi, eh? What do they do?”

“Well my mom is an NP. And my dad does healthcare administration.”

“Healthcare administration? What’s your last name?”

I tell her, and then, as customary, spell it out for her.

“Oh my god! Wait! I know someone with that last name. You know, that last name isn’t very common. Do you know this person?”

She shows me a picture on her phone of a driver’s license: someone with my last name but a first name that I do not recognize.

“No, I don’t think I’m related to this person. Weird, though. It isn’t a very common name around here.”

Then: “Are you an NP?” I ask Jasmine.

“No, an RN. I don’t know if I want to go back to school. And you know they don’t make it easy for brown girls.”

She interrupts her own train of thought when Sadie—an older Black nurse with a thick ponytail and boxy glasses—walks in.

“Uh oh, Massa’s here! Start picking cotton,” she says, pinching her fingers in the air above the table. “Is this enough?”

“You already know you’re in trouble,” Sadie replies with a laugh and the two of them walk out together, their voices trailing off.

The rest of the day is spent first seeing patients all on my lonesome and then going back in with Dr. Geng, who sticks laryngoscopes up their nostrils—taking us all on a Magic School Bus adventure.

People smile and tell me “good luck” on their way back to the waiting room. They say, “I was just telling Victoria this” and “I was just telling Victoria that,” and I’m still adjusting to the weight of it all. They tell me they’re getting better—feeling better. That this or that is still a problem, though. That their father was abandoned at Lincoln Zoo when he was a newborn or that they choke themselves awake at night.

Sometime in the afternoon, Dr. Geng thanks me for my help and relieves me of my duties for a brief lunch break. I go back to the workroom and blink my eyes at the fever-dream feast stacked on the round table like a desert-heat mirage: eight large boxes of pizza and a bowl of salad.

“Can I eat this?” I ask Lily and Maya, who nonchalantly type at their computers.

“You have to wait for Skylar. It’s for her going-away party.”

I nod and go to the bathroom and, somewhere in those two minutes, Skylar has arrived and brought with her a crowd of hungry celebrants. Here’s your five-year gift. We’re gonna miss you. I find myself at the back of the line—craning my neck at the slices from the bottom of the totem pole. Eventually, I make it back to the front and have my chance to ravage through the boxes.

The last patient of the day is a tremoring old man here for his vocal cord injection. I watch his folded hands shake in his lap. The scope hits the back of his throat and lights his mouth up like a jack-o-lantern.

“We’re going to do a little meditation,” Dr. Geng tells him. “Slowly count your breaths. As you breathe in, count one. As you breathe out, count two. Breathe in; three. Breathe out; four.”

I follow along, drifting off.

“Just like that. You’re doing great. Just focus on the breath. Breathe in; five. Breathe out; six.”

Sometimes the only way out is through.

July 11, 2024 - I am starting to find my footing again. When I am told where to meet up in Leaver only thirty minutes before I’m supposed to be there, I zoom with determination.

Today’s good mornings are gentle—they come with smiles and coochie coochie coos. Good morning, our cute little ones. We rotate on the first kiddo. You’ve got a little drool on your shoulder. Be careful what you touch. The second patient, Jasper, is a little baby sleeping on his side, cuddled beneath a zoo animal blanket. There are toys at the foot of his bed, and a cartoon squeaks in the background while his mom watches from her place on the couch against the wall. Then we’re speed-walking back to the ENT workroom.

“You’re in Badi’s clinic?” Steven, a PGY-4, asks Maya—my partner for today—who shuffles at my side. “You’re gonna have fun. Lots of patients, but it goes by quick. He has you take down the history on a piece of paper, and then he just walks out at the end of the day with a big stack for his notes.”

“Yeah, I was wondering how there were thirty-six patients scheduled. Like this patient is scheduled at 8. And this patient. And this patient.”

“That’s low. Forty is standard for him.”

Maya gets her things and then we break off from the main group. “Are you hungry? Let’s go get breakfast.”

It feels almost sacrilege—my first real breakfast of the rotation. I copy her hot bar order—two pieces of bacon and two hashbrowns—and we walk to the clinic physician workroom an hour before the first scheduled patient. On the way up, she teaches me about tonsils and sleep apnea and neck masses.

“If it’s a branchial cleft cyst, it’ll be more midline. But I’m sure you know that.”

I wouldn’t be so sure, I think. Declan—another visiting fourth-year from Ohio—joins us in the workroom.

“Dude, people drive crazy here. I’ve never seen such crazy driving. Like this is the first time I’ve ever seen people drive on the outermost lane on the highway. You know, the shoulder? Like they’ll just be speeding and I think they’re gonna crash right into me and then they just merge right onto the shoulder. It’s the craziest thing.”

“Yeah,” Maya says. “They also drive like that in Detroit.”

“Did you hear about that crazy shooting last week?”

“Yeah, you mean the one right here?” Maya says, pointing out the window.

“No, the one where five people got shot. Two parents and like three kids and only one survived. Well, two survived but one is on ECMO8, so. They said the one that survived got shot in the cheek.”

“Do they know who did it? Like did they catch them?”

“They think it was targeted—a drive by.”

“That’s just so unnecessary.”

Then: Maya dashes out and comes back in with a copy of Dr. Badi’s patient history template. “I just talked to his nurse, Serena. He runs a tight ship. Only write your notes here,” she says, pointing to a tiny box on the page. “And there’s no lunch break, so hopefully you have some snacks. That will help.”

“My home program was really intense,” she then says to Declan. “I lost like ten pounds in a month. You know when you’re so tired that you go to bed instead of eating?”

When the clock hits 8 AM, Maya and I make the hallway-long journey to the clinic rooms. We are greeted by Serena—his senior nurse—and Stella—a newer hire.

“I’m just here to hand out the stickers,” Stella says. “Any questions, defer to Serena. She’s the expert. I’m just here to collect the check.”

“She’s not joking.”

“You have so many stickers,” Maya says to Stella, thumbing through the rolls organized side-by-side.

“That’s my favorite part of the job. If I couldn’t hand out stickers, I wouldn’t be here.”

Like yesterday, I venture into the patient rooms first to scope out the scene and then Dr. Badi—an aged Lebanese man with wise and composed eyes—follows after. Aside from a few minor slip-ups—such as asking if a nine-month-old was wetting the bed—everything goes off without a hitch, and I take notice of my ease talking to parents and their littluns—how much I smile when putting on my baby voice and ripping off stickers.

I’m feeling so good, I see two new patients at once to try to speed things along. When I come out of the second patient’s room, Stella’s staring daggers into me.

“Don’t touch anything on the table. I got yelled at.”

“I’m sorry,” I say to her and then again to Dr. Badi who comes over to investigate why the patient notes are out of order.

“No, don’t worry. It’s okay,” he says, patting me on the back.

Yesterday’s instructions: don’t wait for me to see new patients. Today’s instructions: wait for me. New day; new doctor; new job—catch me if you can. As always, I adapt. This Barbie can go hours without eating. This Barbie smiles through the pain. This Barbie is working away the existential dread.

A little girl with curly hair inches her way out of a room. Her hijabi mom chases after her.

“I don’t want to go in! No, no!”

Her dad—a gigantic man dressed in police gear—comes out and that’s the end of it.

“How come she listens to you?” I hear and then the door is closed.

Another patient: a 2-month-old baby here for a follow up on his recent hospitalization for breathing issues. I communicate to the Spanish-speaking couple through an iPad-bound translator.

“Okay, what’s going on?” Dr. Badi asks me outside the room.

I start: “Admittedly, I have no idea.”

He laughs and softly punches my arm. “Haha, I love that! Don’t worry, it takes time. I’ve been doing this for thirty years. I didn’t know what was going on when I first started. Come, let’s go find out together.”

We run to the audiology office to check that cute little baby David has had a hearing test—they’re a young couple, and I don’t want him to fall through the cracks—and then he sends me off for a break.

“Go get lunch, so they don’t accuse me of starving the medical students.”

My healthiest day at work, I go down to the cafeteria to pick up some hospital poké. When I’m back, we check in on a quiet pre-teen following up on her ear cyst.

“It’s called pilomatricoma. It’s just a growth originating from the hair follicles—completely benign,” Dr. Badi explains. “We were worried that there might be some parotid gland involvement, but her scans look fine.”

And: “We can do surgery for it. It’ll only be a minor incision. The whole thing will probably take around forty minutes.”

And: “You should smile more. You’re cute. You always look sad.”

“She just gets nervous,” her dad says.

Later, Dr. Badi takes me into an empty clinic room. “Okay, time for our mid-day feedback session, since they say we need to have those.

Anyway, you’re doing great. I can tell that you’re very detailed, which is a good thing. Just try to get more focused. Parents will tell you all these things—that they have asthma and a jerking leg or sometimes their nose itches—and you’ve got to sort through the noise and lead them with your questions.”

In my head, I hum along to the tune of “We Are the World.” I am looking our hope right in their bright eyes. The future snores—gets ear infections.

“Stella, how’s it going?” someone asks her as she sighs at the computer.

“It’s going.”

Then: “Be careful,” she says to a little braided girl climbing up a rolling chair. “How about you come down from there and get a sticker!”

The little girl climbs back down and stares wide-eyed at the ransacked sticker collection. She grabs a handful before moving her attention to the critically-low toy container.

“You can get a toy after, but you got to be good for the doctor, okay? Them’s the rules. And then you’ll get more stickers.”

The sticker-obsessed cutie walks back to her grandma, who stands hunched over in the hallway.

Then minutes later: “Can I have more stickers?” she says, running back into the hallway with her previous bounty pasted all over her striped T-shirt.

“You already have three! Only if you’re good—she’s the boss,” Stella says, gesturing to her grandma.

“Please,” she whines.

“No, you have to be good for the doctor, okay?”

Her grandma takes her by the hand and she cries all the way back into their assigned room.

My last new patient: a cute little 15-month-old baby dealing with a painful tongue-tie. The room also holds two slightly older boys running around, a dad holding the baby in his lap, and a mom on her phone sitting quietly in the corner.

“Can you open her mouth for me?” I ask the dad. He lays the baby down on her back and wedges her lips apart against her resistance, precipitating a major crying event.

“Oh no, what did that mean lady do? I didn’t do it—she did,” he says, pointing a finger at me while consoling her.

“Why are y’all touching my baby?” the mom says, steaming behind her glasses. Her point-blank gaze traps me in the palm of her fist. “When you’re out there, can you tell Dr. Badi that he needs to schedule the surgery as soon as possible?”

Then minutes later she’s out in the hall: “You know I’ve been waiting for an hour? And I’ve been very calm and respectful.”

I put my hand on her shoulder and say, “I know, I know. It’ll be soon.”

And then “soon” finally comes. The day: FIN.

On my way out, I listen in: “What should I wear for my date? Nothing?” says Paige—a blonde-haired nurse—with a pitchy cackle.

“You should stay at home and realize all men are trash,” Stella replies.

“No, I hate people. I’m just calling it a date so I can dress up.”

“I hate the apps. It’s like, ‘This is a study in cluster B personality disorders.’ Yeah, I had an app for like three days and then deleted it. Ever since my fiancé beat me up, I’m like, no more, I’m done with this.”

“Well, I didn’t meet my abusive one on an app.”

“I didn’t either. He was just standing there, like, ‘Hey babe, how do you like black eyes? Oh, you like that? Well how do you feel about legally-questionable jobs? Oh, you like that too?’ and I’m like, stop it, you’re baby daddy material here!”

“I have a tendency to get drunk and set up dates and then the next day I have to be like, ‘Sorry, I was drinking, and I’m not actually going on a date with you. Nope, not even ice cream. Nope, sorry.’”

“You know Harper? I’d use her pictures on dating apps to get guys to buy me food. I’d be like, ‘If you really wanna meet with me, I’m here and I’m hungry and you need to order me sushi.’”

“Haha, I need to try that! My last guy, I tried to, like, leave him eight times, and he wouldn’t leave me alone. I just want to be alone. I’ll raise some chickens, get a Zebra. Possibly a peacock. Yeah, I’ll have my own little zoo with my two Great Danes.”

“No, you need a cow. A mini-cow. They’re so cute.”

“But then I’ll need two cows.”

Paige eventually leaves, swapped out with Bailey—a male nurse built like a life-sized Boss Baby—who is also on his way out for the day.

“Aren’t you having so much fun?”

“I hate it here,” Stella says, letting her head fall into her hands. “I’m serious about finding a new job. This is intolerable. I’m ready to quit.”

Bailey sticks an LED flashing magic wand stick in Stella’s face.

“You know those can cause a seizure? I can fake one real good—fall on the floor, roll my eyes, even pee myself. I used to work with this bitchy gay nurse, Dave.”

“Bitchy gay nurse? I didn’t know those exist.”

“Yeah, he once went into a pseudo-seizure patient’s room and was like, ‘No pee, girl?’ Like if you’re gonna make all of us come in, at least put in some more work. And then he’d walk by the patient rooms—like the dementia patients would always scream the last name they had heard—and he would just walk by and say, ‘My name’s Stella.’ And they’d just be screaming, ‘Stella, Stella,’ the whole night.

And then he’d do other stuff, like get on the nurse intercom and say, ‘Stella, Dr. Dick needs you right now.”

Then: Bailey switches out on “Cheer Stella up” duty with Mackenzie.

“I hate bras. Why can’t we just accept that things sag.”

Stella reaches into her scrub top to pull up a tattered bra strap. “I got this bad boy back in ‘12, when I started at the other hospital.”

“I had a bra from ‘07 to ‘15. It had gotten so thin—and it was supposed to be white. God, that’s gross. Okay, bye!”

Then to me: “You did good today,” Stella says and hands me a sticker—Purrific! Surrounded by bad influences all day, I swallow down the urge to beg, “More, more, more!”

July 12, 2024 - In true double-O secrecy, I do not receive my Friday assignment until the night before—at 11 PM, already long after I should have gone to bed. My secret mission: another kiddo good morning with the team.

I play the game of sleep exhaustion. Hi, I’d like to spin the wheel. Applause. The spinner circles through the options: eye bags, death is near, DNR9, dozing off; eye bags, death is near, DNR, dozing off; eye bags. I land on “death is near.” Here come the horns—womp, womp, womp.

I’m back in Leaver, now comfortable with navigating the maze of hallways it takes to get there. I take the elevator up to the fifth floor. Inside: an omnipotent young voice playing on the speakers greets me—First floor! Can you find the scooter?—before sending me off—Have you met Ella the dancing Elk? Going down!

On the way to visit little baby Jasper again, I walk past a strangely out-of-place painting: a faceless girl with bows and roller-skates, one hand holding onto an unseen object—a balloon to lift her out of sight, or perhaps a rope straight up to heaven?

In the room: “Jasper is so cute, aren’t you buddy?” The omnipotent voice—big B for baby—returns in the form of a talking toy. Let’s explore. The team hovers over Jasper with lights and suction tubes. See you next time. Big B has spoken; we make our way out.

We do in-and-out checks of two other kiddos—one status post a tonsillectomy and another awaiting surgery to evacuate a swallowed coin—and then break off. I am alone again today—the only student in Dr. Green’s clinic—but my chest is free of fear. Only twelve appointments, the last of which is scheduled for 11 AM. I already taste the freedom on my tongue—airy and soft.

After thirty minutes of isolation, Jasmine and Dr. Crescas—another surgeon in the department, a woman with chipmunk cheeks and strands of gray shimmering in her acute-angle bang—join me in the physician workroom. Her tongue rolls over the curves of her accent:

“The surrogate wants me to pay $5000 if she loses an ovary or her uterus. But if I pay for that, I’m not gonna pay for the tummy tuck. The tummy tuck was a sure thing, but I’m not gonna tell her she’s making a bad business decision. Because that came from greed. We already agreed on a comprehensive 60k, which was already meant to include everything.”

“This is like a job to have a kid,” says Raima, an NP who has just arrived in the workroom.

“This is insane,” Dr. Crescas continues. “The greed. The chances of her losing a uterus are extremely low. The chances of her having twins are low.”

“I would have took my tummy tuck, baby,” says Jasmine.

“Whatever, bad business decision. What’s really upsetting me is this fluid issue. Maybe I’m not meant to be a mom.”

“No, there are criminals with kids.”

“Yes, did you hear about that woman in Texas?”

“The one who killed her kid?” Raima asks.

“No—well, there are so many stories—but I read it on CNN this morning. You know, during the hurricane, there was this mom that abandoned her kids and ran to Mississippi. A four-year-old and a one-year-old. Just left them at a rest stop. And the four-year-old was found dead, floating. And the one-year-old—he must have had an angel next to him. A truck driver found him—thought that it was a doll but then saw it move. And then he parked half way down the road and saved him.

And I can’t have one and you’re doing this. And I already have a roof and educational books. Life is just so freaking unfair. I should have just had it when I was in residency and damn all those attendings that were sexist pigs! That’s why I tell all of the residents, ‘Go have your baby now.’”

Silence starts to creep in the room and Dr. Crescas bats it away: “In residency, I had some really good attendings—very nice—but then I had ones I really hated. This one guy thankfully left, and I was so happy.

One time I wore a green dress to clinic. Very proper—went all the way down and had a little V-neck but my boobs were not showing. And I had my white coat over it, buttoned up. And I just took it off to go to the bathroom and he had a problem with that.”

“That was because he couldn’t control himself,” says Jasmine.

“Like, if you can’t keep your pee-pee flat, well don’t look. So he sent an email to a female attending saying that we would have to clip our badge here,” Dr. Crescas continues, pressing her badge at the peak of her cleavage. “So that it would be higher.”

Again, silence followed by Dr. Crescas: “My intern year, I broke my hip and tore the labrum. But I was like, there is no way that I can get this surgery during my intern year, so I wait three years until my research year and then get the surgery. And then they contact me saying that they want me to take call10 the next day. And I’m just like, ‘I just had a major surgery yesterday’—especially for someone like me who never took off a day during residency.

So I was in a wheelchair taking call. Yeah, I took call in a wheelchair.”

“You should have called OSHA,” Jasmine says, “That was a case.”

“Six months I was in a brace and a cane, and I operated like that. Then, fellowship year, my director came to me like, ‘You got married?’ And I’m like, you saw I had a ring during my interview. What do you think will happen after two years? And he tells me I’m afraid that it may affect your performance.”

A chorus of clicking tongues.

“I mean, this is the life of a woman surgeon. Things are better now—especially here—but those are the things I put up with.”

It’s fifteen minutes into clinic and Dr. Green is still not here. I wander from the physician workroom to the clinic rooms—once, twice, three times—just to make sure that I’m not in the wrong place.

“I think I’m here with you today,” I say to Jasmine as she exits a patient room.

“Okay, well he doesn’t really have med students do anything. It’s just educational, so no notes or anything like that.”

We walk past Paige, one of the nurses from yesterday. “Jasmine, your hair looks so nice, so voluminous.”

“Yeah, I actually did it today.”

“I wish my hair did that. I went to sleep with my hair wet, and it looks like this. I didn’t even brush it or anything,” Paige says, sliding her sleek, blonde ponytail through her fingers. “I know I’m lucky, but it’s just boring.”

“We just need to give you some curls.”

Back in the workroom, Dr. Green has finally arrived. He is a tall man with a sharp nose and stubble and a bald spot at the crown of his head—smack dab in the middle of his slick curls.

“Hmm,” he says, “It’s strange to have one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine patients check in in our first hour.”

And: “This isn’t my usual template. Someone screwed up the scheduling.”

In the patient rooms, he deep-dives into ear canal after ear canal with his fancy microscope. “Come look, Victoria,” he tells me, and I do, craning my head until I find hidden treasure. Look, this eardrum looks normal. Look, can you see all that amber fluid behind it; okay, now look again, you see how it’s white? Look, come look, this one has some blue in it.

When cleaning out ears, he and Jasmine synergize. Him, asking for tools—suction, alligator forceps, ear powder. Her, handing them over—catching waxy contents on pads of gauze.

In the hallway: “To tell you the truth—with ENT—you sometimes get these people coming in with symptomatic complaints, to be honest. They’re like, ‘Why do I get a random chill in my head when I drink iced tea?’ and I’m just like, I don’t know?”

Also in the hallway: And Wanda’s here. I love Wanda; get the oxygen. You’ve got your glasses on—are you trying to look smart? No, I’ve been feeling dizzy, and I notice that it’s worse when I don’t wear my glasses. Hello dear—uh-uh, fix your face when you look at me. So this patient—what room are we going to, 14?

The three of us—Dr. Green, Jasmine, and I—bounce to-and-fro—from workroom to patient room to workroom and back again. On our umpteenth trip back to the clinic, the mixed stench of poop and air freshener hits all our noses at once.

“Uh-uh,” Jasmine says and takes a detour, leading us around to the other entrance. Dr. Green and I laugh behind her.

“I think that’s Davidson?” he says.

In between patients, I sit with Dr. Green in a nearby room filled with little pamphlets.

“Dr. Green, your next patient is here and she has an iPad full of questions.”

To me: “Okay, another thing about ENT. I’mma tell you straight up, because I love what I do, and I love my patients. But another thing that you see is all these anxious and depressed patients. Like, I’m relatively healthy,” he says, winking at me.

“I get back pain now and then. My foot hurts sometimes when I run. My ears ring sometimes—I don’t do anything about it. But with mental illness—or not just mental illness, but personality disorders—they always identify these external things because they don’t have an internal locus of control. With these people, it’s always about the if only’s. They’re like, ‘If only my ears didn’t ring, if only my boyfriend treated me better, if only I could just get this thing fixed—then that would change everything.’ And they have all these questions and they get mad when you can’t do that for them.

And I don’t mean to be judgmental. When you realize that, it helps you understand your patients better. And your friends. Even yourself.”

Our next patient is a blonde woman with big blue bug eyes and a white mask.

“I just woke up one day and suddenly had this loud ringing in my ears, and it’s honestly really hard to live with. I’m like, how can anyone go on like this?” she says, jotting some words down on her tablet.

Dr. Green sneaks a glance at me, as if to say, “See?”

Three more patients for the day:

A woman with a history of head and neck cancer, who wheezes out the chemo port jutting from her neck, her chin taut and red like a boil ready to blow. So this is the part that’s going to burn, okay? Just count slowly to 10, and then it'll be done. Okay, all done! How is it? Louder? Much better! Good.

A woman whose Picasso-esque craniofacial deformities become clearer once she removes her glasses—yeah, look at her CT scan here, she has some serious sinus issues; see, her maxillary sinus is all crunched. Her tight eyes flap open and quiver as Dr. Green jerks the alligator around in her ears.

A woman with a cochlear implant and an underwater-garble to her voice. No, Dr. Green assures her, you do not have anything stuck in your ear.

Another fly-on-the-wall shift done. I break off my wings—left, right—and pack up my all-seeing eyes.

If only every day were this short.

A Medical Tidbit

Ludwig angina is a type of bacterial infection that occurs in the floor of the mouth, under the tongue. It often develops after an infection of the roots of the teeth (such as tooth abscess) or a mouth injury. This condition is uncommon in children.11

Reasons to Live This Week

Also known as ENT (Ear, Nose, Throat)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sub-internship

https://www.medpagetoday.com/popmedicine/popmedicine/109503

Second-year medical student

https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/chemistry/sevoflurane#:~:text=Sevoflurane%20is%20a%20nonflammable%20ether,be%20used%20without%20intravenous%20anesthetics.

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Crowe-Davis-retractor-or-mouth-gag-with-tongue-blade-grooved-jaws-for-the-incisors_fig2_304910648

Nurse practitioner

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO), also known as extracorporeal life support (ECLS) or heart-lung bypass, is a life-support machine that can temporarily take over the functions of the heart and lungs for patients with severe heart or lung conditions

Do not resuscitate

https://people.howstuffworks.com/becoming-a-doctor14.htm

https://www.mountsinai.org/health-library/diseases-conditions/ludwig-s-angina#:~:text=Ludwig%20angina%20is%20a%20type,condition%20is%20uncommon%20in%20children.